Anode Active Materials (AAM) and Negative Electrode

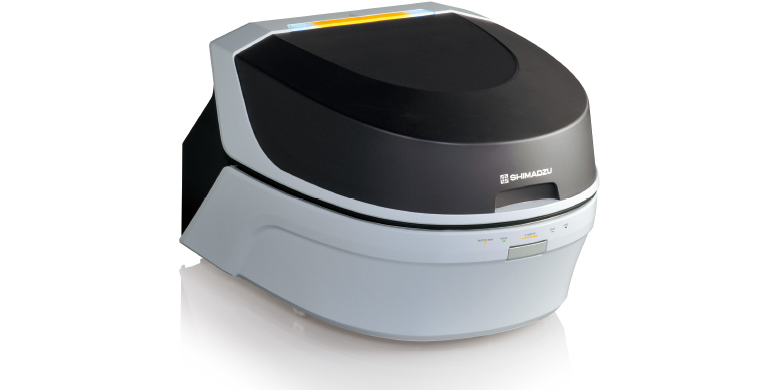

Anode Active Materials (AAM) are predominantly composed of carbon-based materials, with graphite being the most commonly used. The structure and composition of these materials are critical for ensuring the efficient storage (intercalation) of lithium ions during charging. These factors directly influence the key characteristics of the battery cell, including energy density, power density, safety, and service life. To optimize performance and prevent risks, thorough analysis of metallic impurities is essential. Impurities can trigger parasitic reactions that degrade battery performance and, in extreme cases, lead to serious issues such as cell autoignition. Moreover, compliance with European Regulation 2023/1542, which prohibits the use and presence of mercury, lead, and cadmium in batteries, requires careful verification to ensure the complete absence of these substances. For precise detection and quantification of trace metals, the offers advanced elemental analysis capabilities, supporting both performance optimization and regulatory compliance. Additionally, particle size distribution and shape significantly impact ionic and electronic conductivity, which are vital for battery efficiency. As a result, detailed studies of these properties are necessary to achieve optimal performance and reliability. The enables accurate measurement and analysis of particle size and morphology, and the allows to directly measure the strength of these single particles. For broader material characterization, the provides comprehensive material testing solutions, while the delivers high-resolution surface analysis for in-depth understanding of surface properties.

Anode Active Materials (AAM) and Negative Electrode

Anode Active Materials (AAM) are predominantly composed of carbon-based materials, with graphite being the most commonly used. The structure and composition of these materials are critical for ensuring the efficient storage (intercalation) of lithium ions during charging. These factors directly influence the key characteristics of the battery cell, including energy density, power density, safety, and service life.

To optimize performance and prevent risks, thorough analysis of metallic impurities is essential. Impurities can trigger parasitic reactions that degrade battery performance and, in extreme cases, lead to serious issues such as cell autoignition. Moreover, compliance with European Regulation 2023/1542, which prohibits the use and presence of mercury, lead, and cadmium in batteries, requires careful verification to ensure the complete absence of these substances

Additionally, particle size distribution and shape significantly impact ionic and electronic conductivity, which are vital for battery efficiency. As a result, detailed studies of these properties are necessary to achieve optimal performance and reliability.

Solution Highlights

Anode / Negative Electrode Manufacturing

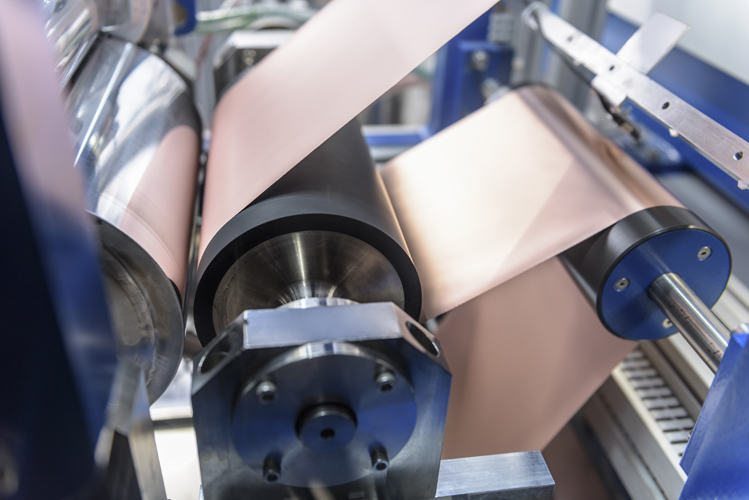

Anodes, or negative electrodes, are produced by coating a current collector—typically made of copper—with electrode material, followed by a drying process. Once dried, the coated material is cut into strips using a slitting process. Evaluating composite electrode materials created through multiple manufacturing steps requires distinct evaluation criteria compared to assessing individual raw materials. This is essential for optimizing the manufacturing process and ensuring consistent quality.

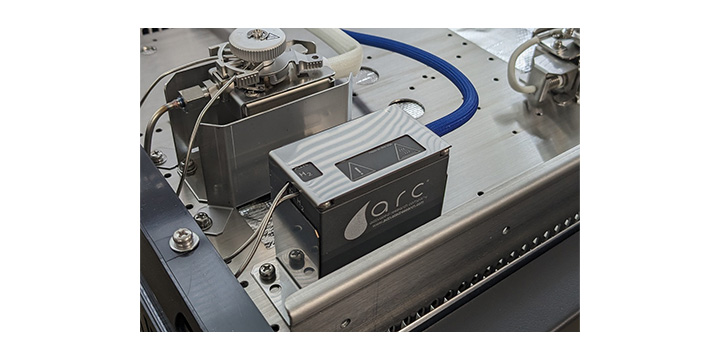

One of the most critical steps in battery production is the formation process, which occurs after assembly. During this phase, the Solid-Electrolyte Interface (SEI) forms at the boundary between the anode and the electrolyte. This thin layer is vital for the proper functioning of the battery, as it significantly influences its lifetime and overall performance. Accurate characterization of the SEI is crucial to understanding and optimizing battery properties and durability.

Solution Highlights

Cathode Active Materials ((p)CAM) and Positive Electrode

Cathode Active Materials ((p)CAM) and Positive Electrode Cathodes are produced by coating aluminum foil with a slurry of Cathode Active Materials (CAM), a binder (e.g., PVDF), conductive carbon, and a solvent (e.g., NMP), then drying and calendering. Common CAMs include NMC and LFP. Because purity, composition, and structure directly determine energy density, power density, and reliability, manufacturers typically verify elemental stoichiometry and trace-metal impurities in CAM powders and aluminum foils with the ICPE-9800 series, monitor residual NMP and other volatiles in slurries and coated electrodes using the Brevis GC-2050, identify unknown organics and degradation products with the GCMS-QP2050, and track organic load in process and cleaning waters via the TOC-L series. Mechanical robustness of the coated foils, tabs, and composite electrodes can then be quantified with the Autograph Precision Universal Tester (AGX-V2 Series), while routine peel, puncture, and compression checks are streamlined by the versatile Autograph AGS-V Series. Integrating these measurements into incoming-material QC and in-process control helps ensure consistent cathode performance, higher yield, and safer operation.

Cathode Active Materials and precursors analysis (CAM & pCAM)

Constructing an efficient cathode is a complex process that involves the careful selection and combination of various materials. A wide range of Cathode Active Materials (CAM) and their precursors, typically based on lithium metal oxides, are available. These include nickel-cobalt-based lithium oxides (NMC) and Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP), each offering distinct properties and contributing to different performance characteristics in the final battery cell.

To ensure optimal performance and safety, a thorough analysis of metallic impurities is essential. Impurities can trigger parasitic reactions that degrade battery performance and, in severe cases, lead to critical issues such as cell autoignition. Additionally, compliance with European Regulation 2023/1542, which prohibits the use and presence of mercury, lead, and cadmium in batteries, requires rigorous testing to verify the absence of these restricted substances.

The inclusion of conductive agents, such as carbon, is also vital for efficient electronic conduction within the cathode. As such, these materials must also be carefully analyzed to ensure they meet the required standards for performance and reliability.

Solution Highlights

Cathode/Positive Electrode Manufacturing

Cathodes, or positive electrodes, are produced by coating a current collector -typically aluminum - with electrode material, followed by a drying process. Once dried, the coated material is cut into strips using a slitting process. Evaluating composite electrode materials created through multiple manufacturing steps requires distinct evaluation criteria compared to assessing individual raw materials. This approach is essential for optimizing the manufacturing process and ensuring consistent quality and performance

Solution Highlights

Liquid Electrolytes and All Solid State Batteries (ASSB)

Electrolytes enable ionic transfer between electrodes during charge and discharge, and in conventional lithium‑ion systems this is typically achieved with complex liquid electrolytes that can suffer from temperature-related performance loss, capacity limits, safety concerns, and aging. To overcome these issues, semi‑solid (gel) and ion‑conducting solid materials are being adopted in next‑generation all‑solid‑state batteries (ASSB), targeting improved performance, enhanced safety, and longer lifespans. Robust characterization accelerates this transition: routine QC of solvent blends and impurities in liquid and gel electrolytes is handled by the compact Brevis GC-2050, while trace and unknown volatile degradation products are identified with the GCMS-QP2020 NX. For solid and gel electrolytes, separators, and composite layers, mechanical integrity—tensile/compressive strength, puncture resistance, and adhesion—is quantified using the Autograph AGS-V Series, supporting safer processing and durable performance.

Electrolytes Characteristics (Liquid and Solid Electrolytes)

The electrolyte is the medium situated between the cathode and anode, containing ions that act as carriers to facilitate ionic transfer. In liquid lithium-Ion batteries, the electrolyte is typically a solution composed of a mixture of ethylene carbonate (EC) or other organic solvents, lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) or other lithium salts, and vinylene carbonate (VC) or similar additives. Since the condition and composition of the electrolyte solution directly impact battery performance, thorough evaluation of its chemical makeup is essential.

In all-solid-state batteries, three types of solid electrolytes are commonly used: oxide-based, sulfide-based, and polymer-based electrolytes. The properties of these solid electrolytes, including particle size, surface characteristics, thermal behavior, and chemical composition, significantly influence battery performance. Therefore, detailed analysis of these attributes is crucial to ensure optimal functionality and reliability in advanced battery technologies.

Solution Highlights

Separator

Separators consist of a porous membrane used to separate cathode anode when liquid electrolytes are used. Separators are mainly made of polyethylene or other polyolefin polymer.

It is important to evaluate the physical and thermal properties of separators and their composition, because separators must not obstruct lithium ion movement during charging-discharging and must be electrically insulative and mechanically strong in order to prevent short-circuiting between positive and negative electrodes. Moreover, the pores close up if the battery becomes hot. Thus, the separators serve to prevent uncontrolled heating.

Solution Highlights

Evaluation of Batteries Manufacturing

Lithium-Ion batteries are produced through electrode fabrication and cell assembly, where materials experience mechanical, thermal, and chemical stresses that influence final quality and performance. To evaluate batteries in their composite state—assembled from multiple raw materials—and to track changes during formation and cycling, manufacturers assess mechanical robustness (tensile, peel/adhesion, puncture, and stack compression) with the Autograph AGS-V Series. Chemical cleanliness is controlled by monitoring residual solvents and process volatiles using routine GC on the compact Brevis GC-2050, while high‑throughput QC workflows are standardized on the Nexis GC-2030. Emerging or unknown decomposition products from electrolytes and binders are identified and quantified via single‑quadrupole GC–MS using either the GCMS-QP2050 or the GCMS-QP2020 NX. To understand interfaces that govern impedance growth and capacity fade, nm‑scale surface chemistry—including SEI and cathode surface states—is mapped by XPS with the AXIS Supra. Together, these measurements ensure consistent product quality and reliability from incoming materials through finished cells and packs.

Electrode Manufacturing

Battery materials are typically produced in sheet form using roll-to-roll processing methods. Cathodes and anodes are most commonly manufactured by coating a current collector with electrode material, followed by a drying process. Once dried, the coated material is cut into strips through a slitting process. Separators, on the other hand, are produced as thin polymer films.

Evaluating composite electrode materials created through these multi-step manufacturing processes requires distinct criteria compared to assessing individual raw materials. This tailored approach is essential for optimizing production methods and ensuring the quality and performance of the final battery components.

Solution Highlights

Cell Assembly

Electrode materials produced through various manufacturing steps are laminated and rolled together before being assembled into a battery cell. Once the rolled materials are inserted into the cell, the cell is sealed through welding and injected with an electrolyte solution.

After assembly, the newly formed cell undergoes an initial charge/discharge cycle using a battery cycler. This process, known as the forming step, activates internal electrochemical processes essential for proper battery operation. Non-destructive analysis of the assembled cell, along with the evaluation of gases generated during the forming and aging processes, plays a critical role in enhancing product reliability and ensuring battery safety.

Solution Highlights

Understand and Study Ageing and Battery lifetime

Batteries do not maintain their initial performance levels throughout their entire lifespan. Over time, various chemical and physical phenomena occur internally during repeated charge and discharge cycles, such as electrolyte degradation and separator clogging. These processes, collectively referred to as battery ageing, require thorough study and understanding to effectively manage battery lifespan and ensure consistent performance throughout usage. To reveal the mechanisms behind ageing, nm‑scale surface chemistry at the SEI and cathode interfaces is mapped by XPS using the AXIS Supra, volatile degradation products and off‑gases are identified by GC–MS with the GCMS-QP2020 NX, routine monitoring of solvents and degradants is streamlined on the Nexis GC-2030, and ionic species from salt hydrolysis and electrolyte breakdown (e.g., fluoride and phosphate) are quantified by ion chromatography with the HIC-ESP. By addressing these challenges with targeted analyses, manufacturers can optimise battery reliability and durability for long‑term applications.

Liquid Electrolyte Ageing

As a complex mixture in charge of the fundamental ionic transfer, liquid electrolyte ageing is one of the bigger contributor in the lose of performances of the battery cells, cycle after cycle.

Degradation of the additive or the solvent can produce various species with a negative effect on the ionic conductivity or on the other cell parts like separator or electrodes. Moreover, electrolyte degradation can also produce gases which can cause major safety issues for the cell. It is thus fundamental to monitor and identify degradation products and process inside the electrolyte.

Solution Highlights

The Solid-Electrolyte Interface (SEI) and its ageing

Solid – Electrolyte Interface (SEI) is a key layer form initially during the forming step between the electrode (anode) and the electrolyte. This layer plays a main role in ionic transfers between electrolyte and electrode and also protect electrode and electrolyte to parasitic reaction.

Nevertheless, cycle after cycle, this layer will see its chemistry and thick change. It will become more thick and less conductive and some poising species can then cross over this protective layer to damage electrolyte of electrode. Follow SEI thickness and composition changes is thus the key to evaluate batterie lifetime.

Solution Highlights

Black Mass and Recycling

Shimadzu provides a wide range of analytical and measuring instruments tailored to lithium-Ion battery applications. These solutions support every stage of the battery lifecycle—from R&D and material characterization to quality control, degradation analysis, and the evaluation of recycled materials such as black mass. For electrolyte and salt studies, ion chromatography with the HIC-ESP quantifies anions, cations, and hydrolysis products, while non-destructive elemental profiling of powders, electrodes, and black mass is performed by the EDX-7200. Volatile solvents, off-gases, and degradation products are identified and quantified by single‑quadrupole GC–MS using the GCMS-QP2020 NX, with automated headspace sampling provided by the HS-20 NX series for robust, repeatable VOC analysis.

Driven by a commitment to sustainability, Shimadzu delivers integrated workflows that help customers optimise materials, improve product quality, and accelerate safe, efficient recycling—contributing to a more sustainable society in all aspects of lithium-Ion battery production and innovation.

Recycling of Lithium-Ion Battery

From a product life cycle perspective, lithium-Ion batteries are ideally reused or recycled to maximize their value and minimize environmental impact. Determining whether a battery is suitable for reuse requires a non-destructive inspection to assess its State of Health (SOH). This ensures that degraded batteries can operate safely if reused.

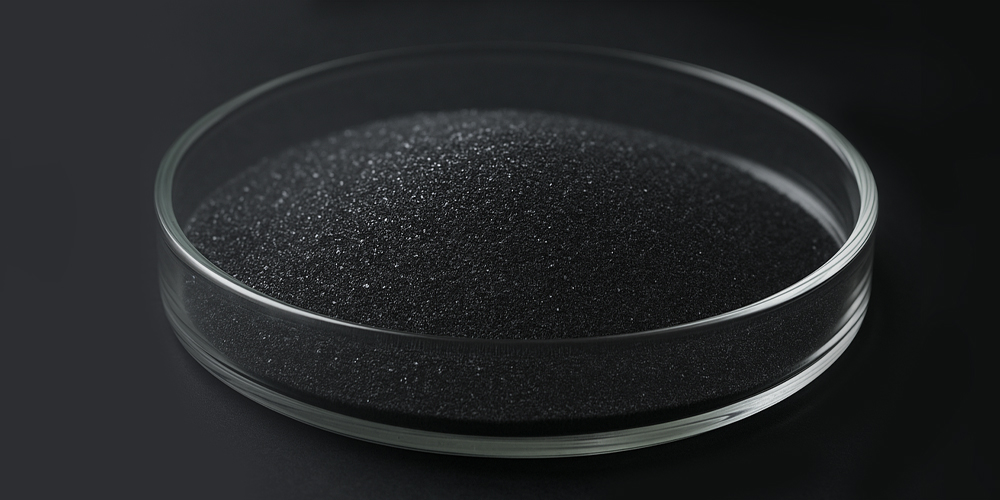

If a battery is too degraded for reuse, recycling becomes the optimal solution to recover high-value materials such as lithium (Li), cobalt (Co), and nickel (Ni). Required under European Regulation 2023/1542, lithium-Ion battery recycling is a complex process that involves treating the crushed remains of batteries, commonly referred to as "black mass."

Analyzing the composition of black mass is essential for assessing the quality of valuable metal powders extracted from used batteries and identifying any contaminants that could interfere with refining processes. This step is crucial for ensuring efficient material recovery and supporting sustainable battery production.

Solution Highlights

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a lithium-ion battery?

Lithium-ion batteries are a type of secondary (rechargeable) battery, as opposed to primary batteries, which can only be discharged. These batteries store energy during charging by intercalating lithium ions into the anode (typically graphite or other carbon-based materials). During discharge, these ions leave the anode, travel through the electrolyte, and return to the cathode. Note that sodium-ion batteries use a similar design in which sodium ions (Na+) replace lithium ions (Li+). Li-ion batteries (LiBs) offer several advantages over other battery technologies, including high energy density and efficiency (they can store a lot of energy at low weight) and long service life. Nevertheless, for some specific applications, other battery technologies—such as redox flow batteries (RFBs) that do not use lithium—can be useful.

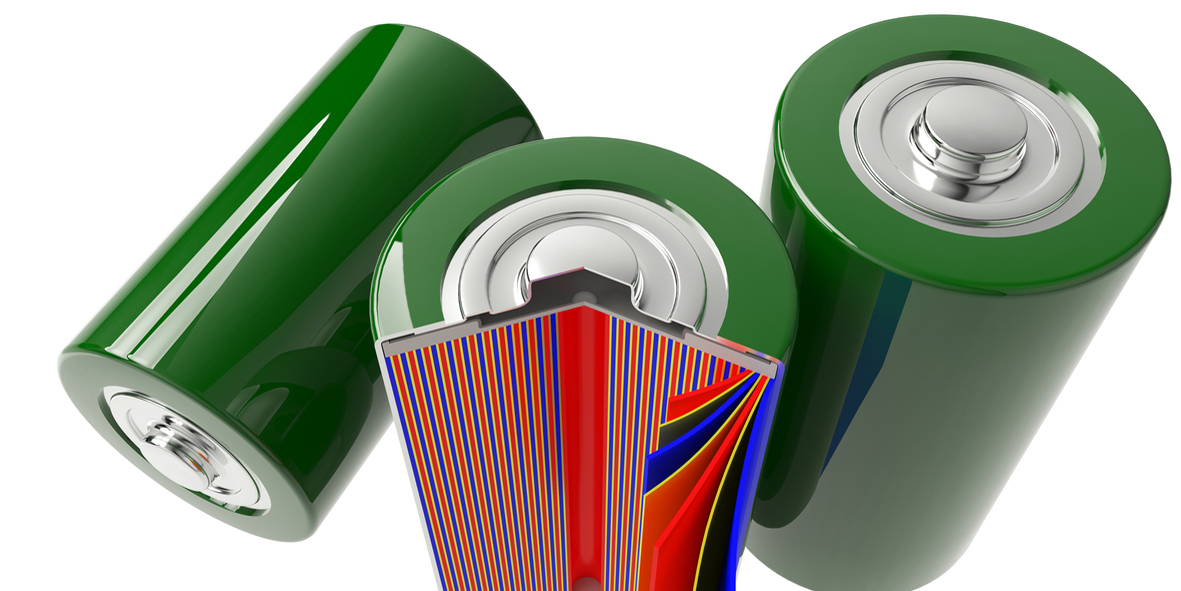

What are the different parts of a Li-ion battery cell?

Regardless of the specific chemistry, a Li-ion battery cell includes the same main parts:

Two electrodes:

- A cathode made of lithium metal oxide (also called cathode active material, CAM), with additives such as a conductive agent and a binder, deposited on a metal conductive layer (current collector).

- An anode, typically graphite, though other carbon-based materials—and even silicon or lithium metal, depending on the technology—can be used (collectively called anode active materials, AAM), deposited on a metal conductive layer (current collector).

An electrolyte that conducts ions between the electrodes. Most electrolytes used today are liquids containing lithium salts dissolved in organic carbonate solvents. Newer LiBs can use semi-solid or solid electrolytes.

A separator (required when the electrolyte is liquid) to prevent short circuits; it is usually a porous polymer that allows Li+ ions to pass.

What are the different types of lithium-ion batteries?

There are several types of lithium-ion batteries that use different cathode active materials (CAMs), derived from different precursors (pCAMs) and, after lithiation, producing different lithium metal oxides. Each CAM family has distinct capabilities and limitations, allowing you to tailor cells to the final application. Common chemistries include NCM (lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide), NCA (lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide), LMO (lithium manganese oxide), LCO (lithium cobalt oxide), and LFP (lithium iron phosphate).

How does a lithium-ion battery work?

The working principle of a LiB is based on lithium-ion movement through an electrolyte (liquid or solid) between two electrodes—one cathode and one anode—kept electrically isolated (by a porous separator when a liquid electrolyte is used). During charging, an external power supply drives electrons from the cathode to the anode through the external circuit, which causes lithium ions to migrate from the cathode to the anode through the electrolyte, storing energy via intercalation. During discharge, the external circuit allows electrons to flow from the anode to the cathode, and lithium ions move from the anode back to the cathode.

Cell, module, and pack—what do they mean?

In the battery value chain, there are different levels of assembly and use, which is why different terms are used for what we commonly call a battery.

- Cell: the basic unit that delivers a certain voltage and current. Common form factors include cylindrical, coin, pouch, and prismatic.

- Module: several cells connected together to reach higher current and power levels, with added components for mechanical assembly as well as thermal and safety management.

- Pack: several modules connected together, capable of storing and delivering large amounts of energy under the supervision of a battery management system (BMS).

Why does my battery lose capacity over time?

With each cycle, a LiB loses part of its initial performance. This is called aging and explains why a battery has a finite, defined lifetime. LiB aging is a complex phenomenon that includes many chemical and physical processes inside the battery—for example, electrolyte degradation, separator clogging, and growth of the solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI) at the anode/electrolyte interface. Characterizing and understanding these phenomena requires chemical analyses, such as chromatographic analysis (e.g., GC or HPLC) of the electrolyte combined with mass spectrometry to identify degradation products.

Why are analytical and mechanical tests important for lithium-ion batteries?

Standard tests for cells, modules, and packs include electrochemical cycling and impedance measurements, but these only tell you about the battery’s status and suggest hypotheses about what phenomena may be occurring. To truly understand the why—such as the causes of aging, failure origins, or the chemical processes inside a battery—analytical testing such as chromatography (GC, HPLC) and elemental analysis (AAS, EDX, ICP) is essential. Being able to determine raw-material composition is also key to ensuring battery performance and preventing impurities that could lead to safety issues. Elemental analyses are therefore critical for anode/cathode active materials and for lithium-salt analysis (raw materials for electrolyte and CAM). Last but not least, mechanical testing to check material resistance to external factors (vibration, shock, etc.) and internal factors (e.g., dendrite growth) is very important to ensure battery safety. Analytical and mechanical testing are therefore essential throughout the battery value chain—from raw materials to pack assembly—for both quality control and research and development.

What is the difference between battery reuse and recycling?

After reaching its expected lifetime as an energy source in a system like an EV, a battery pack may no longer be able to deliver the required performance. These packs can be disassembled into modules and then into individual cells, which are tested to determine their state of health (SOH).

- Reuse: If a cell still has good SOH, it retains potential as an energy-storage device and can be reused in a new module and pack for a different application.

- Recycling: If a cell’s SOH is too low, it cannot be reused for energy storage. Instead, it is dismantled and crushed, and a recycling process is carried out to extract high-value materials from the battery (such as Co, Ni, and organic carbonates). These recycled materials are then used to make new batteries.

What does “black mass” mean?

Black mass is the dark, granular material that remains after lithium-ion batteries are shredded during the initial steps of battery-cell recycling. This black mass is then processed using various methods to extract the high-value metals and molecules it contains, so they can be reused in new battery materials. Composed mainly of carbon from the anode and various metals from the cathode, black mass is a complex mixture and an analytical challenge that must be addressed to manage recycling-process efficiency and maximize profitability.

.jpg)